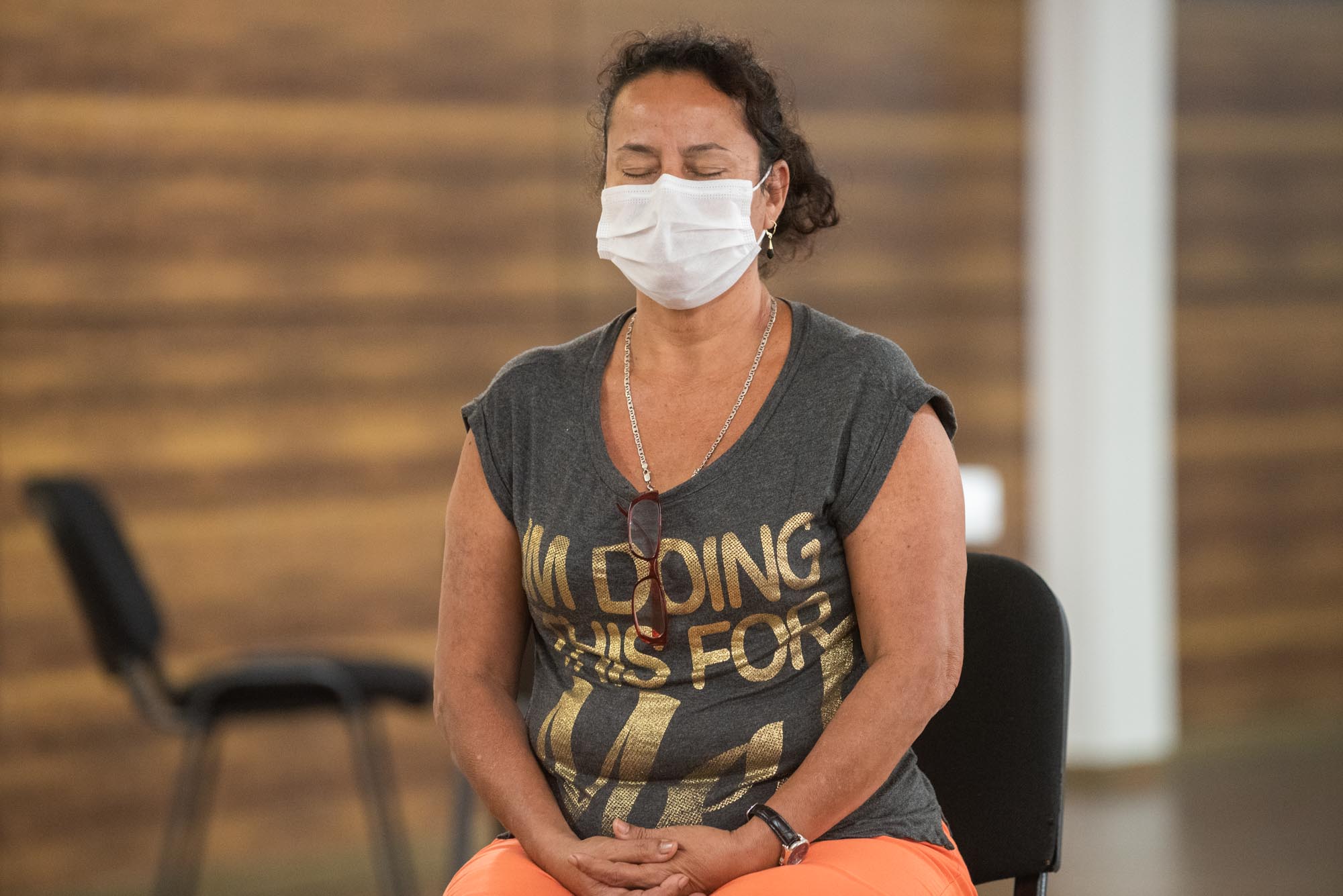

Photography: Cristian Hurtado

Author: Manuela Ramírez, political scientist and coordinator of monitoring and evaluation of the project La voz de dos murales of the Prolongar Foundation.

During these months of confinement I was remembering (and longing for) some of the mindfulness and meditation exercises worked by the Foundation in different scenarios in which I had participated. As a result of this, I was curious to learn more about these topics to put into practice in my home. Apparently I was not the only one, Google Trends recorded an increase in searches for the words “meditation” and “yoga” and their correlation with words such as “anxiety” and “depression” during the first half of 2020 compared to searches for the same terms at the end of the second half of 2019, before the global lockdown resulting from the COVID-19 [1]pandemic.

Although more and more people around the world increase their interest in the subject, even, they are encouraged to practice some meditation technique, still on a personal level I found some resistance to practice it. Because of this feeling, I wanted to identify some beliefs I had about the practice and dig deeper into how true they are. In this blog post I share some findings and reflections on this.

- You have to be experienced to enjoy the benefits of meditation: this belief comes from the idea that meditation is an ancient practice full of complexities and mysteries that can only be mastered by experienced people like Buddhist monks or yogi masters. In reality, all people can meditate and there is no single way to do it. Scientific studies have been carried out with people who do not have any experience in meditation techniques and it has been found that, after a period of training, they begin to experience different benefits of this practice.

The changes reported in these studies occur at three levels: cognitive, physical and psychological. These three levels are interconnected and influence each other. On a cognitive level, meditation practices have reported changes in attention levels, emotional regulation, and self-awareness [2].

On a physical level, the reduction in the production of the stress hormone (cortisol) [2]is reported. There are also studies that point to perceptible changes in the thickness of the brain’s [3]cortical structure, which has the potential to slow down the process of cognitive decline and prevent diseases associated with it.

Finally, at the psychological level, a greater regulation is reported in the automatic thought system, allowing the practitioner to anchor himself to the present moment leaving those repetitive thoughts, usual in episodes of anxiety and depression [3; 4; [5]. Additionally, some studies such as that of Weng, H. Y., et al [6] have pointed out effects on feelings of compassion in practitioners.

- When meditating you have to seek to put the mind “blank”: there is a belief that to meditate you must look for a state in which the mind is in complete silence. This does not work like this for practical purposes. The journal Nature [2] suggests that there are three stages that a person goes through in their practice or acquisition of the ability to meditate: 1. An early stage where the individual encounters the opposite of a “blank” or “silent” space. He must face a current of thoughts, often offline, that appear non-stop in his conscious mind. 2. An intermediate stage in which the individual begins to regulate this current of thoughts through attention without judgment, in other words, observes his thoughts and lets them pass through his conscious mind, often supported by the breath as an anchor to the present moment. 3. An advanced stage in which the individual easily manages [3]to enter deep states of concentration. The brain is like a muscle, one can train it to make it stronger. It is through the exercise of observation and non-judgment that the practitioner can advance at his own pace, not necessarily seeking to put the mind “blank”.

- It takes long periods of meditation to get results: some people insist that they don’t have enough time to devote to meditating, but it really doesn’t need to have a high duration of meditation. Studies such as the one conducted by Tang, Y. et al [4] suggest that 20 minutes a day of meditation has a significant impact on attention, self-regulation, and decreased cortisol production. The digital platform Headspace has also carried out research in this regard. Economides, M. et al., note that just 10 days in a row of the program is enough to reduce stress by 14[7]%.

As you can see, it is worth refuting these three beliefs. Understanding where these (and many others) are born from and how they correspond (or not) to the effects of meditation practice can be critical for people to not only approach these techniques but to persist in their practice. The important thing is to try: for my part, with this search, I managed to expand my knowledge about meditation. I am left with the task of persisting in practice; this is definitely the best way to keep learning.

Bibliography.

[1] H. Ashish Jindal et al (2021) Global change in interest toward yoga for mental health ailments during coronavirus disease-19 pandemic: A google trend analysis. International Journey of Yoga. 14, 2, 09-118. DOI: 10.4103/ijoy.

[2] IJOY_82_20 Tang, Y., Hölzel, K., Posner, M., Ⅰ. (2015). Mindfulness Meditation and Behavior Change. Nature Reviews | Neuroscience , 16, 213–225. DOI:10.1038/nrn3916.

[3] Tang, Y.-Y., Ma, Y., Wang, J., Fan, Y., Feng, S., Lu, Q., Yu, Q., Sui, D., Rothbart, M. K., Fan, M., & Posner, M. Ⅰ. (2007). Short-term meditation training improves attention and self-regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(43), 17152–17156. [4] https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707678104 Brewer, J.

To. Worhunsky, P. D., Gray, J. R., Tang, Y.-Y., Weber, J., & Kober, H. (2011). Meditation experience is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(50), 20254–20259. [5] https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1112029108 Marchand, W.

A. (2014). Neural mechanisms of mindfulness and meditation: Evidence from neuroimaging studies. World Journal of Radiology, 6(7), 471. [6] https://doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v6.i7.471 Weng, H.

And. Fox, To. S. Shackman, To. J., Stodola, D. E., Caldwell, J. Z., Olson, M. C., Rogers, G. M., & Davidson, R. J. (2013). Compassion Training Alters Altruism and Neural Responses to Suffering. Psychological Science, 24(7), 1171–1180. [7] https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612469537 Economides, M.,

Martman, J., Bell, M.J. et al. (2018) Improvements in Stress, Affect, and Irritability Following Brief Use of a Mindfulness-based Smartphone App: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Mindfulness 9, 1584–1593. DOI: 10.1007/s12671-018-0905-4.

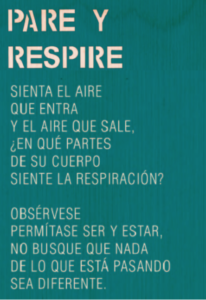

Start by taking some conscious breaths, placing yourself in the present and perceiving the changes you register in your body as you recall your experiences around the pandemic. Record the sensations, emotions, and thoughts that arise. If you dare, and hopefully you will, the invitation is to create a collage*

Start by taking some conscious breaths, placing yourself in the present and perceiving the changes you register in your body as you recall your experiences around the pandemic. Record the sensations, emotions, and thoughts that arise. If you dare, and hopefully you will, the invitation is to create a collage*